Full-Stack Content Design

Maybe you’ve seen people in other fields refer to themselves as “full-stack” practitioners. What they mean is they’re able to contribute to the success of a project at every stage of the work, beginning to end, front to back.

Full-stack marketers, for instance, can gather data, analyze results, design experiments, run tests, create a complete marketing strategy, and do the tactical work of executing it. Full-stack engineers cover a similar breadth: backend, frontend, security, performance, testing, quality assurance. From soup to nuts, they can do it all.

Full-stack content designers play a strong role at every stage of the game, too: research and brainstorming, determining strategy and scope, sketching out flows, testing for usability and accessibility, proofreading and polishing the final result, measuring success and iterating based on the results. Soup to nuts. You can do it all.

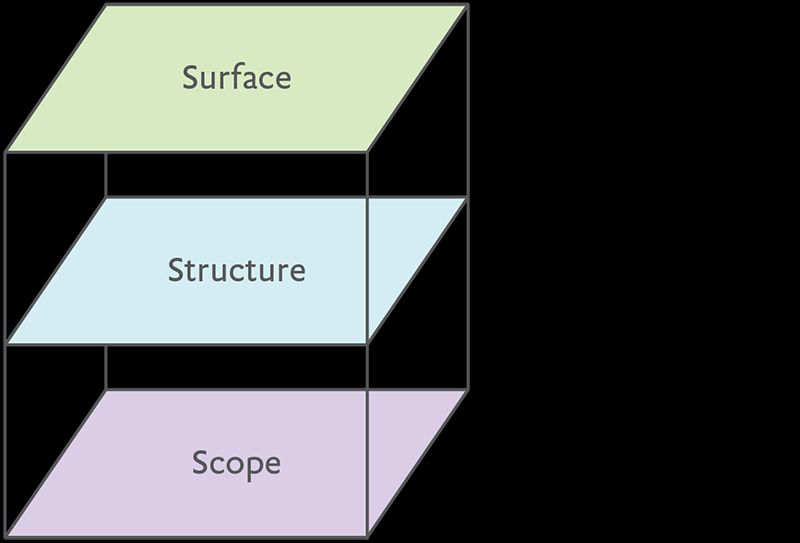

To illustrate this range of contributions, I’ve reimagined the classic “Layers of UX” popularized by designer Jesse James Garrett (http://bkaprt.com/ccd12/01-01/, PDF). Full-stack content design has three layers: Scope, Structure, and Surface (Fig 1). Each layer involves different types of content work: from level-setting and discovery, to creative output, to polishing and perfecting, rinse and repeat.

That’s what full-stack content design is. It’s not really about different stages of a chronological process, or different components of a final user experience. It’s about the practices and people involved in creating digital content. Power up those people, invest in those practices, and you empower your process.

So what does this full-stack content design look like in practice? Let’s take a closer look at each layer in turn.

Scope

The first layer is the place where everything starts (or should start, at least). It’s the part of the process where you explore the problem space, discover what’s possible, home in on your approach, and plan for everything that comes next in the project.

A content designer might be involved with a number of different activities in the Scope layer, usually across three areas of focus: research, problem definition, and strategy and scope.

Research

Content designers often work alongside researchers and analysts to write questions and scripts; conduct interviews; and parse, analyze, and present the results. And since content designers tend to be highly attuned to language and meaning, we often pick up on words, phrases, and cognitive pathways that others might miss. We hear it when users insist on a certain metaphor to describe what they’re trying to do, and can craft interface copy that will match their mental model.

Working in partnership with researchers can be magical. The researchers I’ve worked with have often been delighted by the fresh perspectives a content person can bring to their work. Finding one or two researchers who love working with you can be a great start to establishing a full-stack content practice.

Problem definition

Out of research comes the work of problem definition: working alongside product managers to articulate the problem the team is trying to solve. While the product manager often has a clear vision for this, a content designer can memorably capture it in the form of a written story, loosely illustrated storyboard, or user journey map.

Many teams start out trying to solve a different problem than the one that actually emerges from their research. That’s not meant as a criticism—it’s part of the process. You start in one place, do some research, and then refine your approach. That’s why it’s important to get very good at articulating the problem as you see it from the start, so you know just what it is you’re refining as the research results start to roll in. Content designers help write the story of the problem, and then rewrite it over time.

There are many different ways a team might create a shared story to describe the core problem, such as a user journey map, a long-form narrative story, an illustrated storyboard, or a set of cartoons. They’re all slightly different ways of pulling data points and details into one clear and compelling narrative arc for you and your team to rally around.

Clear and crisp problem definition is particularly important when you’re working on a product with a broad and deep footprint, with teams that value rapid iteration and experimentation, or when coordinating work across multiple independent, autonomous teams on different pieces of the same cross-product user flow. Without clear problem definition, you might end up with different teams taking different stabs at the same problem; but with it, you retain small-team autonomy while keeping your goals and efforts aligned. Crafting a compelling story is also key for getting buy-in from leaders or stakeholders to move ahead with the project.

Strategy and scope

Part of the process of problem definition is deciding where to draw boundaries around your efforts. By corralling the project’s purview and explicitly leaving aside what you won’t be trying to solve, you can help your team avoid scope creep and stay focused.

Deciding on the scope of the project is in itself a strategic move. You’re deciding that this, not that, is the challenge you’re going to solve. A content designer can help a team make this decision clearly, and document it in a way that’s easy for them to remember and share. A well-articulated scope, along with clear project definition, will help determine the strategic moves this project demands.

Structure

The Structure layer is where you start working on the organization, categorization, and hierarchy of ideas. It’s where you begin designing your content to best meet users where they are without overwhelming, distracting, immobilizing, or annoying them.

Content designers will work with their team—often a mix of designers, engineers, information architects, and others—to present the solution to the problem with a focus on usability, learnability, and accessibility. These three areas often overlap, because they are mutually reinforcing, interwoven, and really inseparable at heart.

Usability

Usable content is designed with a careful eye toward how much cognitive load each step or stage carries, and creates consistency across the experience with the patterns the user has experienced elsewhere (in your product or in similar experiences in their life). Usable content makes sense to the user in the context of their own world.

This means your content uses metaphors, symbols, and language that already resonate with your audience. Usable content is inclusive content—you don’t use words or elements that would only be comprehensible or welcoming to someone from a certain background, religion, gender, or class.

Learnability

Learnable content carefully considers which concepts might require explanation, clarification, or active practice to learn, and how to offer users the chance to learn them. The sequence, weighting, separation, combination, and organization of ideas, objects, actions, and assets are all factors in learnable content.

- It’s important to consider what other experiences are already in the product (or are being worked on right now) and how those experiences might interact with or affect the experience at hand. As the resident content practitioner, you’re likely to have a more holistic view of how different angles of the user experience come together across the whole product; the Structure layer is the best time to contribute that perspective.

- On a finer scale, you want to make sure the language and images you’re planning to use match up with what’s used elsewhere in the product. What metaphors or mental models are at play at other points in the experience? How might those metaphors extend to this project? How might they break down?

- It’s often useful at this stage to assemble a simple inventory of the nouns (objects) and verbs (actions) most often used throughout the experience that are relevant to this project. Rather than undertake a full content audit, you might just gather a list of the objects and actions you’re dealing with here. How do they fit (or not fit) the story you’re trying to tell?

Accessibility

Your content won’t be usable or learnable if it’s not accessible, too. Designing your content for accessibility first will make it more inclusive, regardless of user circumstance, ability, or need.

Font size, color contrast, plain language, adaptability to screen readers, and much more all go into designing accessible content. Words need to be readable, in the sense that the user needs to be able to see and read the letters on the screen; and the text needs to be written at a reading level that optimizes comprehension. Text written at a sixth- or seventh-grade reading level is generally the most easily understood by all users, regardless of education level, industry, or background. Use the Resources section at the end of this book to learn more about who needs accessible content (spoiler alert: it’s everyone) and how to write, structure, and design it.

You may come across people who resist your efforts to keep content at an accessible reading level. They may say you’re “dumbing it down” or something equally offensive. You can tell them from me that the only thing that’s “dumbed down” about accessible content is having an outdated, narrow, closed-minded idea of what “accessible” means.

Test early, test often

A common mistake at this stage is to get too invested in the words and images you’re using to organize your design. Teams and individuals can easily latch on to words, images, naming conventions, and mental models that make more sense to them than to the user, which is why it’s important to keep on testing and iterating with real users throughout the life of a project.

At this point, remember that your content is provisional, even placeholder content. Think of it as “low-fidelity” content you will refine over time. Some teams make it a practice to keep the images in early designs deliberately sketchy, unfinished, or at a low resolution, and to set the text in Comic Sans or something equally off-brand as a visual reminder that the content is provisional and subject to change.

Surface

The final Surface layer is where the content is refined and finalized. You already know which concepts and ideas are most important, and when and how they should be encountered and met. Content designers usually work alongside designers, marketers, support reps, and salespeople to make sure the experience they’ve designed aligns with the house style guide; fits into the larger user narrative arc; and is as easy as possible to understand, market, demo, sell, and support.

Proofread and polish

This is where UX writing and illustration come to the fore. You’ve been creating and testing low-fidelity content as part of the content design process so far. Now it’s time to finalize your verbal, visual, and structural choices, and make them consistent with your house style in terms of spelling, grammar, punctuation, and form.

It’s helpful at this stage to refer to some of your earlier work to inventory the words, images, and metaphors used across the rest of the product or experience to ensure your final product is consistent with them. If you’ve introduced any new terminology, concepts, or conventions, now’s a good time to add them to your style guide and other internal glossaries or tools.

Voice and tone

It’s also a good time to inspect your content for any voice or tone wrinkles, and to smooth them right out. Ensure that your words, images, and ideas are consistent with your brand voice, and that you’re using the right tone for the situation at hand.

I like to think of voice as defining who you are—you’re always you—while tone is how you behave in different situations. For example, I might define my own voice as friendly, helpful, quirky, and kind—but I’ll present those aspects of my personality in different (and hopefully appropriate) ways, depending on whom I’m speaking to (my mother, my best friend, or the Queen of England) and the context of our conversation (a phone call, a dinner party, or getting a life peerage conferred).

You might notice that these late-stage activities on the Surface are the ones many people outside the content community tend to think we spend most (if not all) of our time on. But when you’ve been present and active at each stage of the game, the people you work with will have seen with their own eyes how important a role content plays from beginning to end.

Start Where You Are

You may feel you’re stuck at the top of the stack, focused primarily on the Surface layer of content work. If you’re on a product team, that means you’re mostly spending your time on interface word choice and making minor adjustments to voice and tone. If you do marketing, tech writing, or internal communications, it might be more about copywriting, editing, and proofreading for house style. It’s important work, and we tend to excel at it.

The first step in the full-stack mindset shift is accepting the reality of the top of the stack. While your natural impulse may be to bang on pots and pans and fight for a seat at the table farther down the stack, it’s often more effective to start where you’re already having an impact—right in the Surface layer.

It sounds counterintuitive, but hear me out. If you’re stuck in an endless loop of proofreading and polish, start with the people you work with on that: designers, marketers, salespeople. They already know and trust you. You have a foundation of credit with them. These folks are likely to be your first converts—the content champions you’ll enlist on your team.

Why not start by training these enchanting people to do some of this Surface work for themselves? Not all of it, naturally. But surely you can entrust some of the proofreading and polish to a group of enthusiastic trainees.

Moving a little Surface work off of your plate frees you up to go deeper into the stack. If you’re currently buried in work at the top of the stack, and you don’t enlist others’ help, you’ll never get that chance. And if nobody gets to see the deeper work you can do, they won’t think to ask it of you in the future. It’s a vicious cycle.

Hoarding your work also runs the risk of leaving talented people untapped. Literally every team I’ve ever worked with has had a handful of content enthusiasts lurking just under the surface, if you just give them a scratch. If you encourage and empower them even a little, these hidden content champions will surprise you with what they can do.

The goal isn’t to never do Surface work again. It’s to give yourself options. When you equip other people to do this work, too, you give yourself the gift of choice. You can choose to let them do it, or you can jump in and help out. There will always be lots of Surface work to be done, so you’ll never stop the cycle if you don’t find a way to let some of it go.

The downside is that you will no longer be the lone, magical wordsmith who works wonders behind closed doors. Sharing your skillset may erode some of the mystical glow around content design. And that’s not a bad thing.

Because then you’ll be free to rebrand yourself from magical wordsmith to problem definer, scope and strategy wrangler, accessibility advocate, and so much more. It’s a simple question of bandwidth and branding.

Strike Up the Band

I’ll say it again: you’ll never get the chance to do the deeper stack work if you’re swamped with Surface work that only you can get done. And if that’s the only type of work people ever see you do, that’s all that people will ever think you can do.

That’s why the next step in this process is to help the people you work with recognize what good content looks like, understand the value of great content to them in their roles, and learn how to do at least some of that work for themselves.

And the way we do that is by getting everybody to sing the same song.